In the liturgical calendar of the Society of Jesus, January 3 is the Solemnity of the Holy Name of Jesus, our titular feast. Toward the end of his life, the great American Jesuit theologian Avery Dulles gave a lecture entitled “The Ignatian Charism at the Dawn of the Twenty-First Century,” which I think is as relevant today as it was nearly two decades ago. Dulles’s gift as a theologian was to clarify complex issues and get at the heart of the matter. The talk can be found in the collection of Dulles’s McGinley Lectures given at Fordham, Church and Society. Here are the final three paragraphs in which Dulles reflects on the Jesuit charism today:

“The Society can be abreast of the times if it adheres to its original purpose and ideals. The term Jesuit is often misunderstood. Not to mention enemies for whom Jesuit is a term of opprobrium, friends of the Society sometimes identify the term with independence of thought and corporate pride, both of which Saint Ignatius deplored. Others reduce the Jesuit trademark to a matter of educational techniques, such as the personal care of students, concern for the whole person, rigor in thought, and eloquence of expression. These qualities are estimable and have a basis in the teaching of Saint Ignatius. But they omit any consideration of the fact that the Society of Jesus is an order of vowed religious in the Catholic Church. They are bound by special allegiance to the pope, the bishop of Rome. And above all, it needs to be mentioned that the Society of Jesus is primarily about a person: Jesus, the Redeemer of the world. If the Society were to lose its special devotion to the Lord (which, I firmly trust, will never happen) it would indeed be obsolete. It would be like salt that had lost its savor.

“The greatest need of the Society of Jesus, I believe, is to be able to project a clearer vision of its purpose. Its members are engaged in such diverse activities that its unity is obscured. In this respect the recent popes have rendered great assistance. Paul VI helpfully reminded Jesuits that they are are religious order, not a secular institute; that they are a priestly order, not a lay association; that they are apostolic, not monastic, and that they are bound to obedience to the pope, not wholly self-directed.

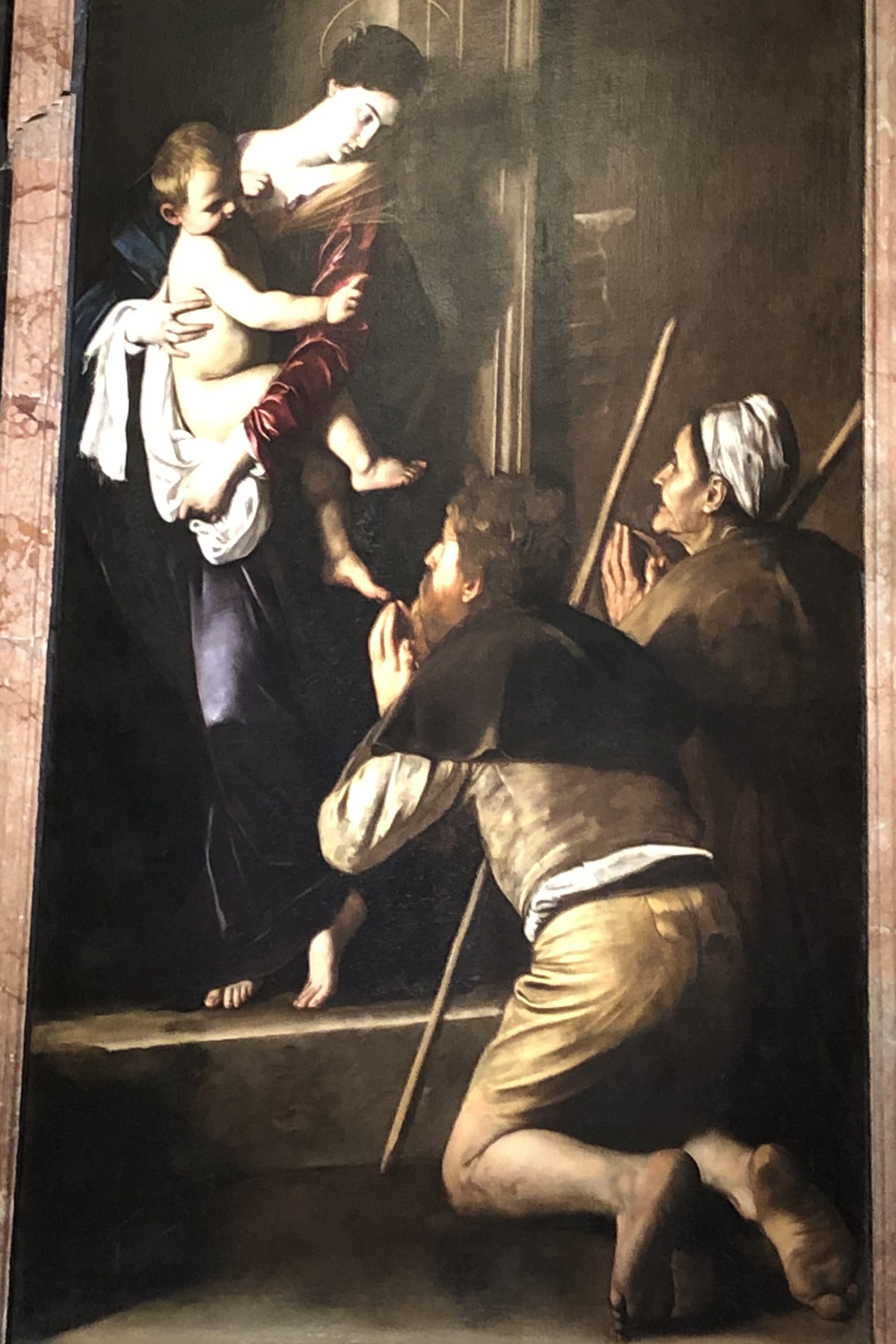

“Pope John Paul II, in directing the Jesuits to engage in the new evangelization, identified a focus that perfectly matches the founding idea of the Society. Ignatius was adamant in insisting that it be named for Jesus, its true head. The Spiritual Exercises are centered on the Gospels. Evangelization is exactly what the first Jesuits did as they conducted missions in the towns of Italy. They lived lives of evangelical poverty. Evangelization was the sum and substance of what Saint Francis Xavier accomplished in his arduous missionary journeys. And evangelization is at the heart of all Jesuit apostolates in teaching, in research, in spirituality, and in the social apostolate. Evangelization, moreover, is what the world most sorely needs today. The figure of Jesus Christ in the Gospels has not lost its attraction. Who should be better qualified to present that figure today than members of the Society that bears his name?”

Avery Cardinal Dulles, S.J.

November 29, 2006