As I noted at the beginning of the month, November is a month dedicated to praying for the dead. It is also a time in which the readings begin to take on a somewhat apocalyptic flare. The theme of the end of things echoes with the changing seasons; at least in the northern hemisphere, this is the time when fall turns into winter.

It might seem macabre to dedicate a particular season to considering death, but it doesn’t have to be. In any case, not thinking about death will not prevent it from happening to each one of us. One reason to pray for the dead, as I wrote a few weeks ago, is to help them on their journey through purgatory. Another is to give us the proper attitude toward life. The things in this world are temporary; our relationship with God is eternal. We should plan accordingly.

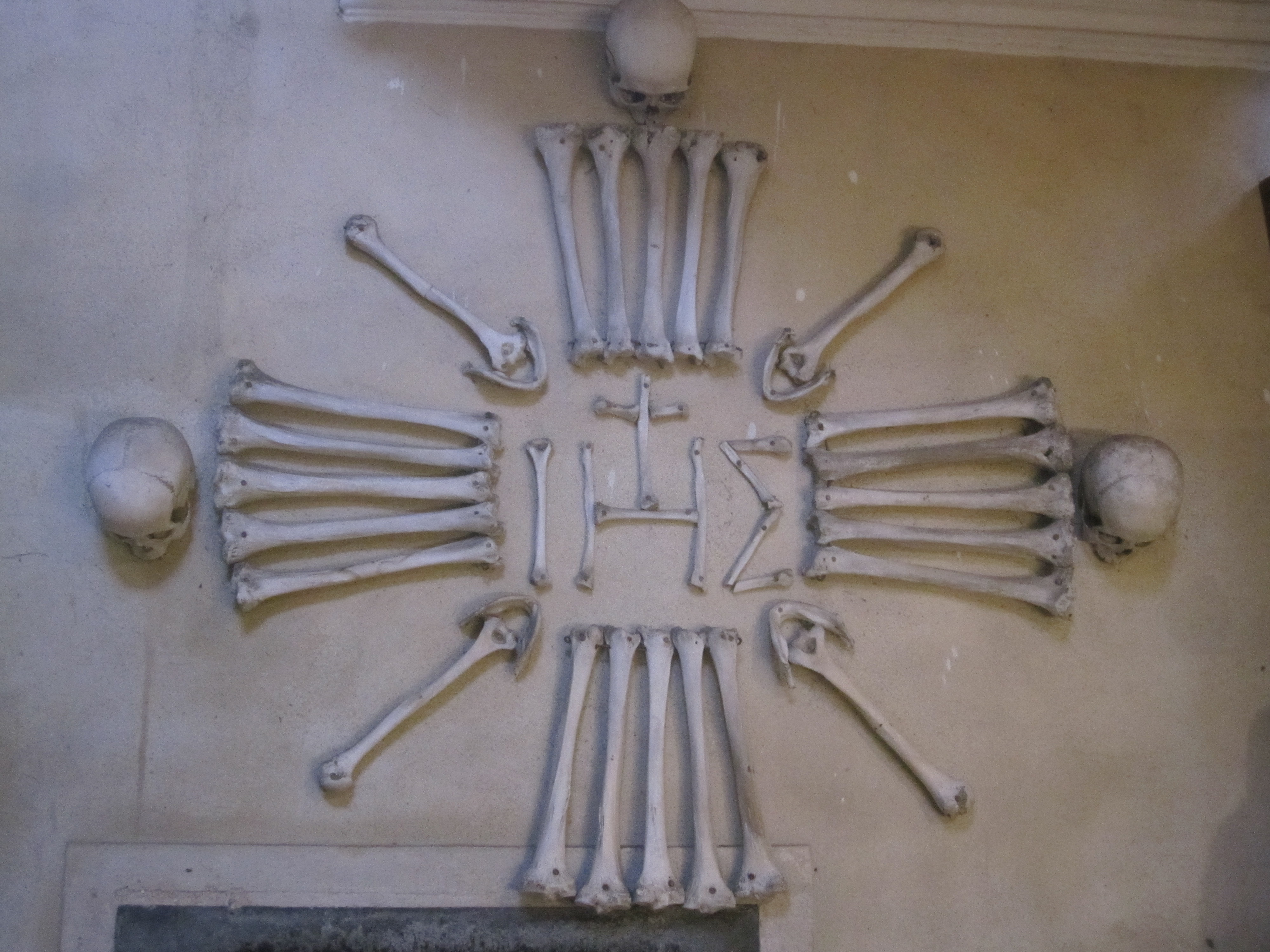

There’s a great Christian tradition of meditating on the four last things–death, judgment, heaven, and hell. The first two will be faced by everyone; the latter pair is either/or. Traveling, I’ve come across a number of sights dedicated to the theme of memento mori, stark reminders of our mortality. To someone with modern sensibilities, some of them are, I admit, more than a little odd. But I like sniffing out weird stuff when I travel, so I’ve seen quite a few.

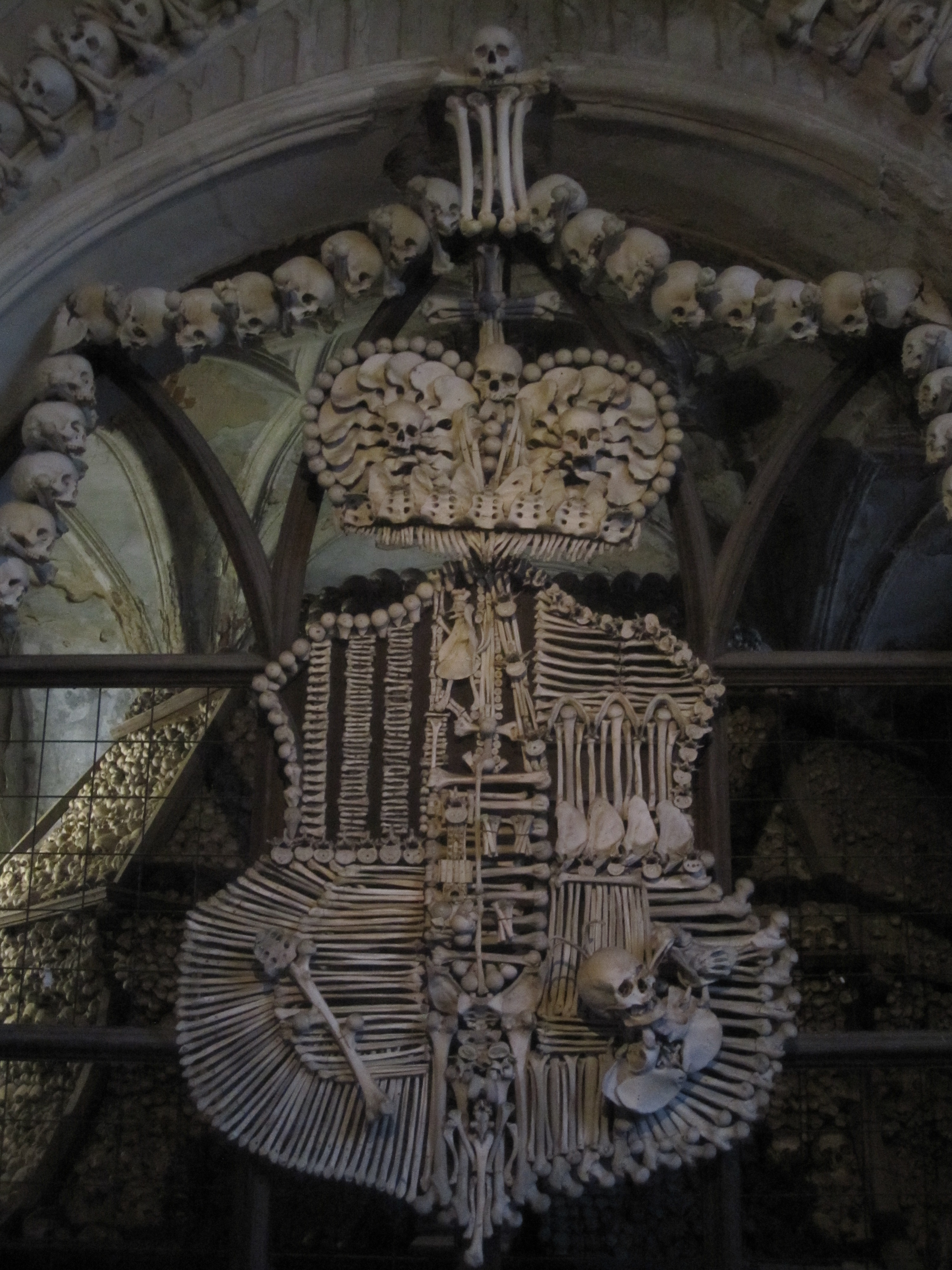

Perhaps the most striking of these monuments of mortality I’ve come across is in the small Czech town of Kutná Hora, once a rich mining center and home to a massive 18th century Jesuit college, it also houses the Sedlec Ossuary, a chapel built under All Saints Church decorated entirely with bones. The aesthetic is decidedly baroque–garlands, vases, cornices, cherubs, spires on a baldacchino, bows and ribbons. All made of human bones–jaw bones, femurs, ribs. The cherubs are playing with skulls. I can’t say it’s the interior design scheme that I’d choose.

But there it is, a top sight attracting crowds of tourists. Sure, there’s a macabre draw to the place, but I think its fascination goes deeper than that. In another such sight here in Rome (the Capuchin crypt on Via Vittorio Veneto), the place’s message is made explicit in a sign placed among the skeletons, “What you are, we were. What we are, you will be.” Such sights are not just fascinating, but compelling. Compelling in a way that makes whether they are cheerful or attractive or in good taste totally irrelevant.

We’re drawn to these memento mori sights because what they say is true.