Homily for the 17th Sunday of Ordinary Time (A)

When he was a young priest St. Philip Neri shaved off half his beard in order to counteract vanity. St. Simeon the Stylite lived on a small platform on top of a 50-foot tall pillar in Syria for over 30 years. Another St. Simeon (of Emesa), known as the Holy Fool, walked through town with a dead dog tied around his waist. St. Catherine of Siena lived for weeks on nothing more than the hosts she received at communion. Shortly after his conversion, St. Francis stripped naked in front of the bishop of Assisi. St. Francis Xavier, a Jesuit, tending plague victims in a hospital found himself holding back out of fear of contracting the disease. (This one’s a little gross.) So he scraped the back of one of the sick men he was tending, gathered up a handful of puss, and put it in his mouth. And St. Maximiliam Kolbe, a Polish Franciscan priest imprisoned in Auschwitz, asked his Nazi guards if he could take the place of a man condemned to die in order to save that man’s life and give up his own instead.

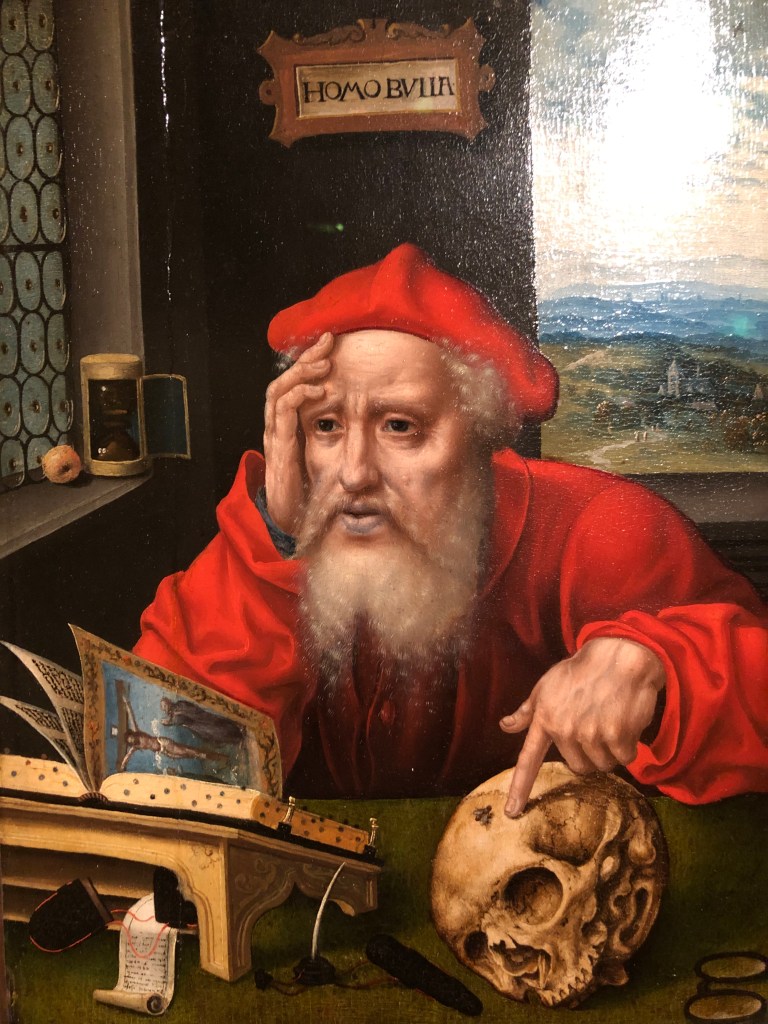

I am not recommending that you try any of these things at home. Instead I want to ask you a question: are these saints foolish or wise? And if they are wise, then what does wisdom really mean?

In our first reading, the young King Solomon is praised by God for asking for the gift of wisdom. But what makes someone wise? Wisdom is not the same as memorizing lots of facts or accumulating knowledge. You could go home and memorize the phonebook, but I’d consider someone who just looked up phone numbers as needed actually to be wiser. We probably know people—perhaps grandparents—who received relatively little formal education but we’d consider wise. And I’ve known a plenty of people with PhDs who were not nearly as smart as they told you they were.

Continue reading “Fools for love: homily for the seventeenth Sunday of Ordinary Time”