One of the most remarkable places in this remarkable city of art is the Contarelli Chapel in the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi, home to the St. Matthew trilogy of Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. Three paintings–The Conversion, The Inspiration, and The Martyrdom of St. Matthew–tell the story of the life of the saint, from his improbable calling to his death. The paintings are full of artistic drama, reflecting the artist’s own spiritual struggles and his attempt to find his place among Italy’s artistic greats.

The paintings date from early in Caravaggio’s career (1599-1600), when he was at the apex of his success in Rome. Only a few years after painting the St. Matthew trilogy, however, Caravaggio’s artistic career was sabotaged by his own unruly passions–he was forced to flee Rome after murdering a man in a brawl. As I’ve argued before, the fact that Caravaggio sinned so spectacularly does not negate a deep thirst for God or his spiritual and sacramental sense. In fact, as so often happens, awareness of his sin may have heightened the need the artist felt for redemption. In one of his later works, which he painted while in exile for his crime, David holds the head of Goliath–who bears Caravaggio’s own anguished face.

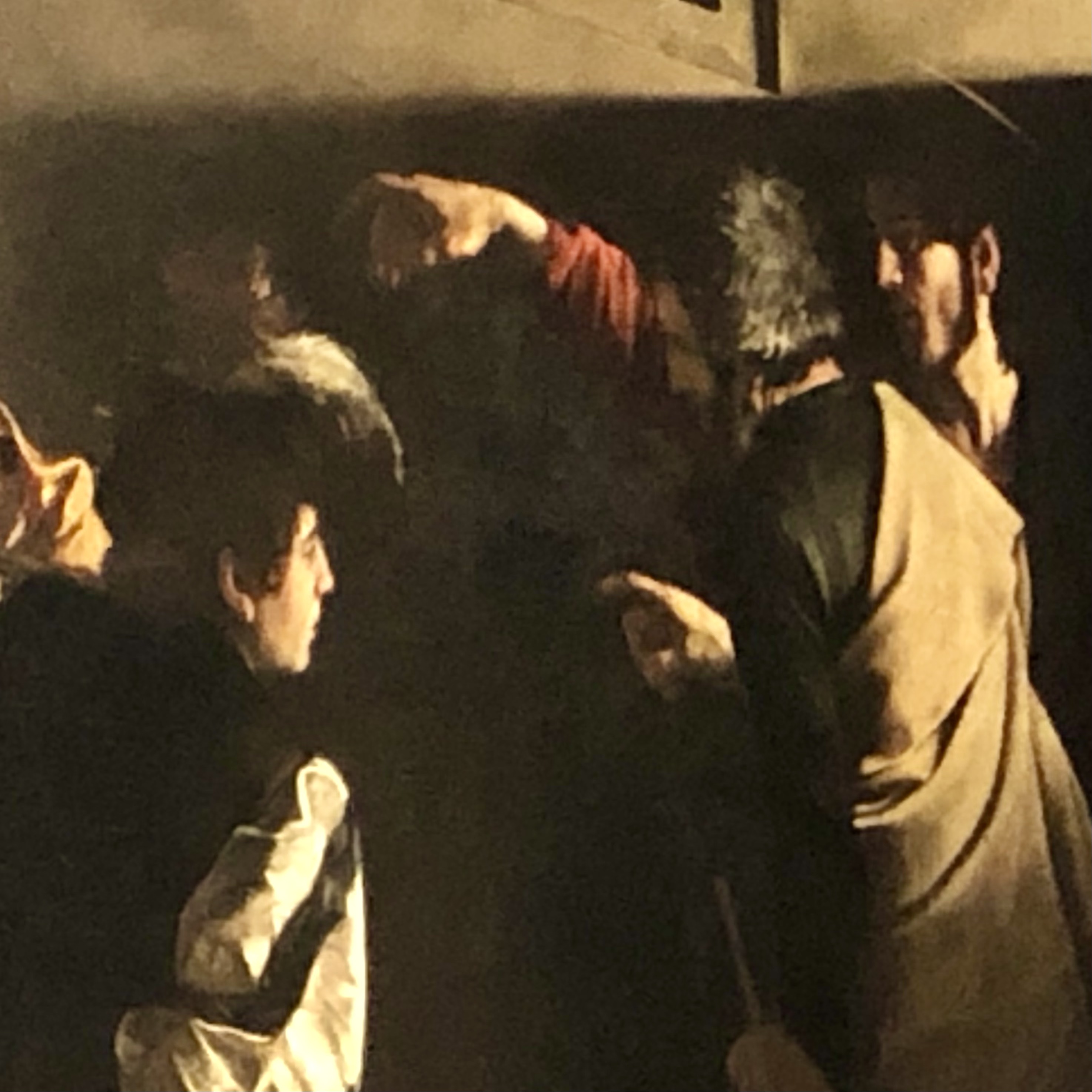

Conversion also drives the “plot” of Caravaggio’s St. Matthew cycle. The first of the paintings, The Call of Matthew, depicts the moment when Jesus walks into Matthew’s customs post where the tax collector sits among cronies, coins spread over the table in front of him. Light shines in from a window just over the Lord’s head and hits Matthew straight on as Jesus raises his hand and points an unrelenting finger, as if to say, “You.” The tax collector’s own finger rises to his chest and his eyes widen, as if to respond, “Who? Me?” Or perhaps he is trying to distract the Lord’s gaze by pointing to the ne’er-do-well next to him, whose eyes are still fixed on the coins. In either case, the painting captures all the passion and confusion of the call to conversion–the unrelenting gaze of God, the instinctual avoidance and doubt of the sinner who is called. Does Matthew think himself unworthy? Shy away from relinquishing the wealth he knows? Hesitate when truth itself dissolves the shadows of ambiguity he has woven around himself? Probably, all of the above.

Those familiar with Rome’s greatest Renaissance masterpiece–as Caravaggio most certainly was–might recognize something familiar in the shape of Christ’s outstretched finger. It mimics the most famous outstretched hand in art, that of God about to touch Adam in the moment of creation on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Conversion, Caravaggio must have known, means nothing less the being created anew. But Matthew’s hand is turned toward himself, not reaching back to the Lord, because the greatest obstacle to the new creation God offers is our own self-absorption.

The middle panel of the trilogy, my own favorite, shows an older, slightly more wizened Matthew writing his Gospel. In it Caravaggio shows off what is most distinctive in his style–the bold simplicity of the evangelist’s red and orange robes against a dark and empty background, the intensity of the apostle’s eyes, his rough bare feet. And in this painting too, the artist echoes Michelangelo’s earlier work. Above Matthew, an angel descends, delivering inspiration. Another finger is outstretched as if to point, but this time the angel is using it to count on his fingers. It’s as if he is ticking off a list of precisely the things he wants included in the Gospel. Inspiration and creation again. And just so we don’t miss the connection to the Sistine Chapel, the angel appears in a swirl of robes which are puffed out into exactly the same shape as the robes trailing God the Father in the Creation of Adam, a shape roughly that of the human brain. And what could be more fitting? Wisdom itself creating man in his image, and Wisdom again dictating the words of new life.

The final painting depicts the death of Matthew. It is full of figures and movement, to the point that some critics have derided it as busy. Matthew is murdered at the Easter Vigil while baptizing catechumens; thus the saint is depicted in priestly robes while the catechumens, semi-nude, are preparing for immersion. It is the moment in which Matthew himself will experience the martyr’s “baptism” of which Jesus speaks (Mk 10:38). At long last, his conversion to the Lord, begun with his calling in the first panel, will be complete. From directly above Matthew another angel reaches down, this time not to dictate inspired words but to offer him a palm branch, symbol of martyrdom and salvation. And Matthew’s hand, which in the first painting pointed doubtfully–almost accusingly–at himself is now open to receive it. It is a moment of awful violence–his assassin towers over him, dagger ready to plunge–but it is also a moment of fulfillment and salvation.

Matthew’s hands stretch out–not unlike Jesus on the Cross–and at last the former tax-collector can grasp the new life to which he has long been called.

And just a reminder, if you haven’t done so already, consider subscribing to this blog:

The Creation of Adam… Michelangelo portrayed the image of God as Leonardo da Vinci. So why did he choose do this. Sandro Botticelli, Simonetta Vespucci, Domino Ghirlandaio and even Michelangelo are all featured in the God-pod.

LikeLike