Homily for the 17th Sunday of Ordinary Time (A)

When he was a young priest St. Philip Neri shaved off half his beard in order to counteract vanity. St. Simeon the Stylite lived on a small platform on top of a 50-foot tall pillar in Syria for over 30 years. Another St. Simeon (of Emesa), known as the Holy Fool, walked through town with a dead dog tied around his waist. St. Catherine of Siena lived for weeks on nothing more than the hosts she received at communion. Shortly after his conversion, St. Francis stripped naked in front of the bishop of Assisi. St. Francis Xavier, a Jesuit, tending plague victims in a hospital found himself holding back out of fear of contracting the disease. (This one’s a little gross.) So he scraped the back of one of the sick men he was tending, gathered up a handful of puss, and put it in his mouth. And St. Maximiliam Kolbe, a Polish Franciscan priest imprisoned in Auschwitz, asked his Nazi guards if he could take the place of a man condemned to die in order to save that man’s life and give up his own instead.

I am not recommending that you try any of these things at home. Instead I want to ask you a question: are these saints foolish or wise? And if they are wise, then what does wisdom really mean?

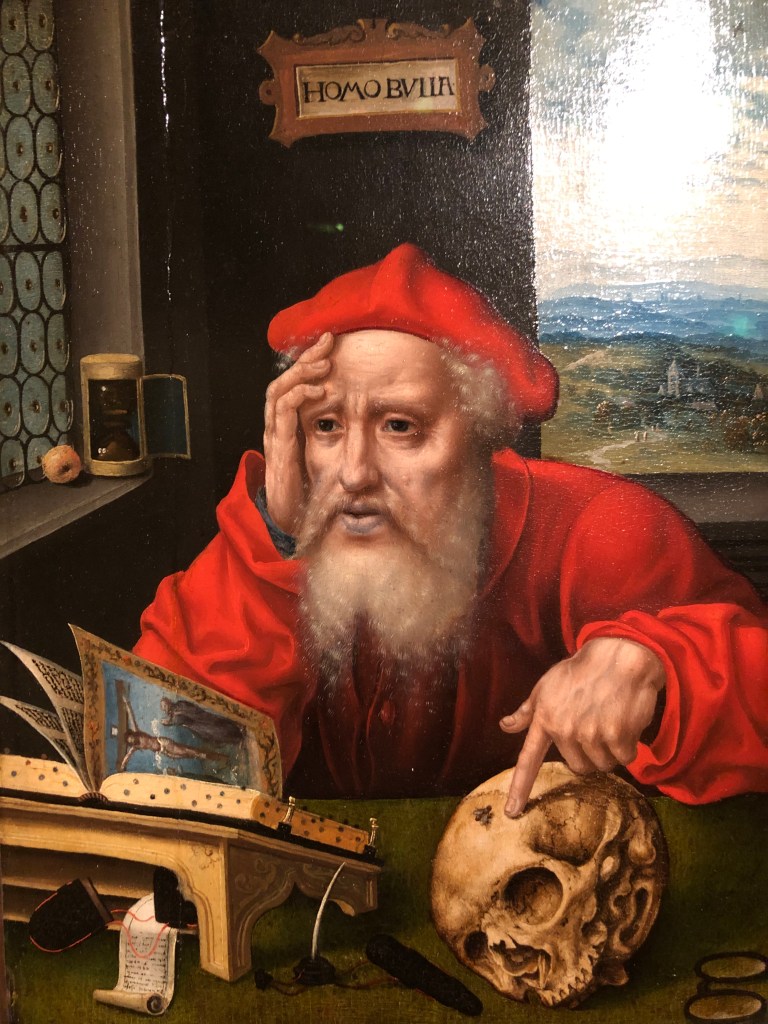

In our first reading, the young King Solomon is praised by God for asking for the gift of wisdom. But what makes someone wise? Wisdom is not the same as memorizing lots of facts or accumulating knowledge. You could go home and memorize the phonebook, but I’d consider someone who just looked up phone numbers as needed actually to be wiser. We probably know people—perhaps grandparents—who received relatively little formal education but we’d consider wise. And I’ve known a plenty of people with PhDs who were not nearly as smart as they told you they were.

Learning and knowledge can contribute to wisdom, but the heart of wisdom is expressed, I believe, in what Jesus gets at in the Gospel. Wisdom has to do with having our priorities right. The test of real wisdom is the question, “What is most important to you?” And if we think about wisdom in this way, we understand how the weird things certain saints have done through the ages seem foolish but express a deeper wisdom. What each of those saints I mentioned was trying to demonstrate was that those things which we normally think are very important—our public reputation and social standing, our physical comfort, our physical health, even our earthly life—are nothing compared to our relationship with God and the life he promises in heaven.

Again, I’m not suggesting we imitate those actions I mentioned earlier—you’ll notice my beard is still intact on both sides—but they are meant to make us uncomfortable so we will question our priorities. The point of Jesus’ parables about the treasure in the field, the pearl of great price is clear enough: our faith in him must come first in our lives and change the value of all our other priorities. Professing the Catholic faith must make a difference in our lives. It must make a difference in how we think and what we do. If we believe there is, in fact, a life after this one, then Maximilian Kolbe giving up his earthly life for someone else is not foolishness but the ultimate wisdom. If we believe that we will be judged by God, then worrying about the judgments of others, of fashion, of public opinion, of keeping up with the times, seems rather foolish. To be a little more concrete—and maybe to make you a little uncomfortable—three years ago when I was full time in parishes, I was always amazed at the reasons people gave for skipping Mass. “Oh, we had a high school basketball game.” Now, I’m just going to be blunt: unless Jesus Christ has returned to earth to coach high school basketball, skipping Mass for a game is a sin.

The reason I bring this up is not to scold but because I want to draw attention to why. It’s not because there is anything wrong with sports; sports are great, they’re fun, they help us learn teamwork, help us develop healthy habits, teach us about commitment. But the question is: commitment to what? What are our priorities? When there’s a conflict, which priority comes first?

There is a right and a wrong answer to that question. God must always come first. Putting him anywhere else than in the number one position is real foolishness.

I do realize that keeping God in that number one position is not easy because there are so many other priorities in our lives jockeying for that top spot, shouting at us, trying to get our attention. So I’d like to end with a thought, that is, I hope, an encouragement.

Most of us who are adults and at least some of the teenagers have had the experience of falling in love. Falling in love is one of those things that will change your priorities. The world starts to look different when you’re in love. We do things we thought we never would because love changes our priorities. This month I saw a high school friend for the first time in several years. This guy, one Christmas when we were both home from college and catching up, says to me out of the blue, “Tony, what do you know about Armenia?”

And I said, “Former Soviet republic by the Black Sea. Why?”

And he said, “Because I’ve met an Armenian girl, and I’m moving to Armenia.” Love makes you do things that seem a little crazy to those on the outside; it rearranges your priorities. And thank heavens it does! Because what a delight it was for me a few weeks ago to see this friend and his charming wife and their three beautiful children when they visited—from Armenia.

Our Catholic faith, at its heart means this: falling in love with God and letting that love rearrange all of our priorities. It’s a mature love, to be sure, that involves obligations as well as ecstasy, as any serious long-term relationship does. But that’s not even the really good news; that’s not even the encouraging thought I want to leave you with.

Falling in love, as I said, involves doing things you otherwise wouldn’t, sacrificing other priorities, other good things for the ones we love—even in the most extreme cases giving up our lives for the ones we love. And that’s the reason the wisdom of love, the logic of love, looks like foolishness to those who’ve never experienced it. So being Catholic means falling in love with God. But it means something even before that. It means God has fallen in love with us. God—wisdom itself—has made himself a fool for love.

Readings: 1 Kings 3:5, 7-12; Rom 8:28-30; Mt 13:44-52

St. Isaac Jogues Catholic Church

Rapid City, South Dakota

2017