Readers of this blog will know that one of the delights of living in the center of Rome is that a Caravaggio is never more than a stroll away. I’ve written about the great spiritual insight in Caravaggio’s Matthew cycle in the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi. Last year, I reflected in The Catholic Thing on why Caravaggio so resonates with contemporary viewers after visiting an extraordinary exhibit of his work in Palazzo Barberini.

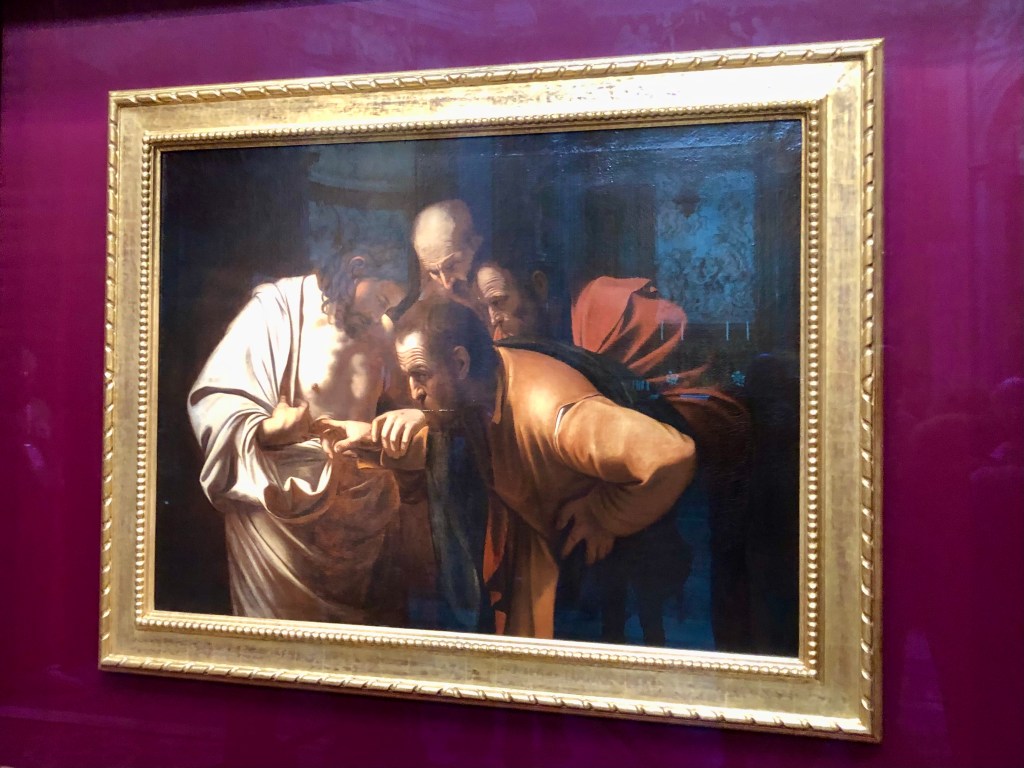

At the tail end of the Jubilee I caught another extraordinary exhibit, albeit of just one Caravaggio, at Sant’Agnese in Agone. The work, The Incredulity of St. Thomas (1602-7), was on loan from a private collection in Florence. It’s a work full of drama and humanity and shows Thomas wide-eyed while inserting his index finger into the Risen Lord’s side. Jesus himself is utterly serene as he guides the doubting apostle’s hand toward his torso. (A nice detail is that the Lord’s face seems a bit sunburned, while his body is not.) Two other apostles look on over Thomas’s shoulder with both concentration and astonishment.

Continue reading “Doubting Caravaggio’s Doubting Thomas”